I’m pretty sure I’ve found the song of the summer, and it just so happens that this same song has killed off a central strategic pillar of several music streaming services.

I’m pretty sure I’ve found the song of the summer, and it just so happens that this same song has killed off a central strategic pillar of several music streaming services.

First of all, let’s start with some background. Pharrell’s “Freedom” is an irresistibly infectious hit (la la la la… la la la la la—good luck getting that out of your head). And, blurry legal issue aside, Pharrell’s been on an uninterrupted A-list hit streak for a few years now.

As well, Apple spent a lot of time and money to let people know that he was going to drop an exclusive on Apple Music to launch the whole enterprise putting it everywhere from press releases to their big TV spot to the social channels of everyone from Apple to Pharrell himself.

Now we’re a week and a half into the track, and it’s really starting to catch the mainstream with everyone from the USA Today to Kanye talking about it.

But here’s the rub: now that the track is catching on everywhere, it’s available everywhere. As soon as everyone started to like the exclusive, the exclusivity was gone.

This raises some pretty fundamental questions not just about this effort from Apple but also about music exclusives overall.

First, in a world where even hit songs from huge artists take at least a week to really catch hold, is there any benefit to a brand or streaming service to have it for the first few days when a track is just starting to take off? Does your average (Spotify) user care? More pointedly, is there anyone who does care about having the track in those first few days who won’t go through the trouble of finding it on YouTube or another not-so-legal destination?

Second, what is the residual value of an exclusive track? In a month’s time, will anyone remember that Apple had the track exclusively for a few days? Or is the only value realized if you keep doing exclusives over and over again, leaving you chasing the proverbial rabbit around the race track to make any of it matter?

Third, how much of your brand do you need to uncomfortably contort to promote exclusives? Apple found this out the hard way– Zane Lowe played the song repeatedly during the time that the song was exclusive to Beats One radio… but the trouble is, that’s the opposite of the point of Beats One Radio, and completely contrary to pretty much everything Zane Lowe stands for (Twitter complained plenty about this). To promote the exclusive, Apple had to compromise the core beliefs of the service. Tricky.

These three questions clearly demonstrate that Apple’s last week with Pharrell casts some pretty big doubts on the exclusive windows that are presumed to be a pillar of the strategies of streaming services.

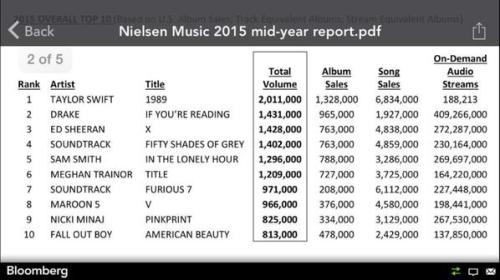

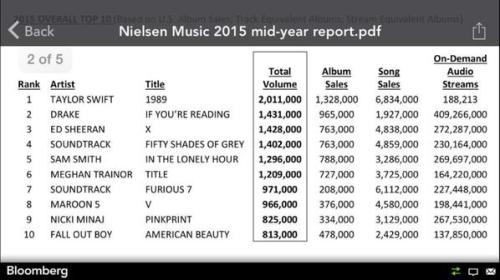

Can Taylor-esque boycotts leave marks on Spotify and scare Eddy Cue? Yes, but these scenarios are limited to the nearly singular kinds of artists that yield as much market power as she does (see below for the source of Taylor’s singularly stunning market power).

To be fair to Apple, exclusives aren’t a strategy of theirs as much as they are an enabler of their curation strategy. Apple has bet big on curation over algorithms, but their experience with Beats Music taught them that anonymous curation doesn’t work: playlists made by anonymous editors won’t work among mainstream audiences… but playlists made by celebrities just might. So, for Apple, celebrity exclusives are an ingredient that turbo charges their curation strategy.

But, for others (read: Tidal), the implications are far more worrying. From the first moments of their re-launch, Tidal has ignored the high fidelity sound that had been their niche trademark, and bet big on exclusives of everything from songs to videos to playlists. In fact, the only place you can currently stream Prince tracks is Tidal. But you didn’t know that until just now, and that’s the point.

One of the biggest stars on the planet just invalidated one of the few strategic paths that have been identified by streaming services. If not exclusives, what should they do?

More on that in the days to come.

As everyone reads about how Star Wars closed out the biggest global opening in history (even accounting for inflation), it’s interesting and important to consider why 2015 was– in many ways– the year of the blockbuster.

As everyone reads about how Star Wars closed out the biggest global opening in history (even accounting for inflation), it’s interesting and important to consider why 2015 was– in many ways– the year of the blockbuster.